Why the Death Penalty Is Not Better for Families

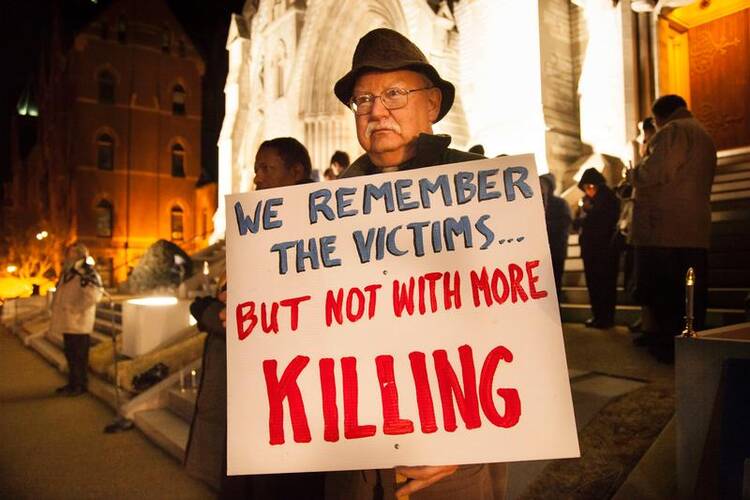

Deacon John Flanigan holds a sign during a vigil outside St. Louis Academy College Church building Jan. 28 ahead the execution of Missouri death-row inmate Herbert Smulls of St. Louis. (CNS photo/Lisa Johnston, St. Louis Review)

Deacon John Flanigan holds a sign during a vigil outside St. Louis Academy College Church building Jan. 28 ahead the execution of Missouri death-row inmate Herbert Smulls of St. Louis. (CNS photo/Lisa Johnston, St. Louis Review)

Over 1,000 state prisoners are on death row in America today. A Justice Section official recently said that many of them are exhausting their appeals and that we may soon "witness executions at a rate approaching the more than iii per calendar week that prevailed during the 1930's."

On Capitol Hill, meanwhile, there is an endeavor to restore the expiry penalty every bit a punishment for certain Federal crimes. A bill to accomplish this was canonical by the Judiciary Committee in a 13-to-vi vote final twelvemonth when conservatives lined upward for the death penalty and liberals declaimed in vain against it. Yet one demand not be a certified liberal in order to oppose the death penalty. Richard Viguerie, premier fundraiser of the New Right, is a firm opponent of capital punishment.

Some of the arguments against the death penalization are substantially conservative, and many others transcend ideology. No ane has to agree with all of the arguments in order to reach a conclusion. Equally President Reagan has said in another context, doubtfulness should e'er be resolved on the side of life.

Nor need one be "soft on crime" in order to oppose the death penalty. Albert Camus, an opponent of capital punishment, said: "We know enough to say that this or that major criminal deserves hard labor for life. But we don't know enough to prescript that he be shorn of his future—in other words, of the chance we all have of making amends."

Only many liberals in our state, past their naive ideas nigh quick rehabilitation and by their support for judicial discretion in sentencing, have washed much to create demand for the death penalty they abhor. People are correct to be alarmed when judges give light sentences for murder and other violent crimes. It is reasonable for them to ask: "Suppose some crazy guess lets him out, and members of my family are his side by side victims?" The inconsistency of the judicial system leads many to support the capital punishment.

There are signs that some liberals at present understand the trouble. Senators Patrick Leahy (D., Vt.) and Edward Kennedy (D., Mass.), in opposing the death-penalty bill approved past the Senate Judiciary Committee, are suggesting as an alternative "a real life sentence" for murder and "heinous crimes." By this they mean a mandatory life sentence without possibility of parole. And if nosotros adopt Chief Justice Warren Burger'southward proposal near making prisons into "factories with fences," perhaps murderers tin pay for their prison room and board and also make financial restitution to families they have deprived of breadwinners.

With these alternatives in mind, allow us consider ten good reasons to oppose the death sentence.

1. There is no way to remedy the occasional mistake. One of the witnesses against the death punishment earlier the Senate committee last twelvemonth was Earl Charles, a man who spent over three years on a Georgia death row for murders he did not commit. Some other witness remarked that, had Mr. Charles faced a system "where the legal apparatus was speedier and the death penalty had been carried out more expeditiously, we would now be talking well-nigh the late Mr. Charles and bemoaning our error."

What happens when the mistake is discovered later on a homo has been executed for a law-breaking he did not commit? What do we say to his widow and children? Do we erect an apologetic tombstone over his grave?

These are not idle questions. A number of persons executed in the Us were later cleared by confessions of those who had really committed the crimes. In other cases, while no ane else confessed, there was great doubt that the condemned were guilty. Watt Espy, an Alabamian who has done intensive research on American executions, says that he has "every reason to believe" that x innocent men were executed in Alabama solitary. Mr. Espy cites names, dates and other specifics of the cases. He adds that there are similar cases in virtually every state.

We might consider Charles Peguy'southward words almost the plow-of-the-century French case in which Capt. Alfred Dreyfus was wrongly convicted of treason: "We said that a single injustice, a single criminal offence, a single illegality, especially if it is officially recorded, confirmed...that a single law-breaking shatters and is sufficient to shatter the whole social pact, the whole social contract, that a single legal crime, a single dishonorable deed will bring about the loss of one'south honor, the dishonor of a whole people."

ii. There is racial and economical discrimination in application of the death penalty. This is an old complaint, but one that many believe has been remedied by court-mandated safeguards. All v of the prisoners executed since 1977—one shot, one gassed and iii electrocuted—were white. This looks similar a morbid kind of affirmative action programme, making upwards for past discrimination against blacks. But the five were not representative of the expiry-row population, except in being male. Nigh 99 percent of the death-row inmates are men.

Of the 1,058 prisoners on death row by Aug. 20,1982, 42 pct were black, whereas near 12 pct of the The states population is black. Those who receive the death sentence still tend to be poor, poorly educated and represented past public defenders or court-appointed lawyers. They are not the wealthy murderers of Perry Stonemason or Agatha Christie fame.

Discriminatory application of the expiry penalty, also being unjust to the condemned, suggests that some victims' lives are worth more than others. A study published in Crime & Malversation (Oct 1980) found that, of black persons in Florida who commit murder, "those who kill whites are near twoscore times more than probable to be sentenced to death than those who kill blacks."

Even Walter Berns, an articulate proponent of the death penalty, told the Senate Judiciary Committee terminal year that uppercase penalty "has traditionally been imposed in this country in a grossly discriminatory mode" and said that "it remains to be seen whether this state can impose the death penalisation without regard to race or class." If it cannot, he alleged, and then death penalty "will have to exist invalidated on equal-protection grounds."

It is quite possible to be for the death penalty in theory ("If this were a merely globe, I'd be for it"), but against information technology in do ("It's an unjust, crazy, mixed-upward world, so I'one thousand against it").

3. Awarding of the death penalization tends to exist arbitrary and arbitrary; for similar crimes, some are sentenced to expiry while others are not. Initially two men were charged with the killing for which John Spenkelink was electrocuted in Florida in 1979. The second man turned state's evidence and was freed; he remarked: "I didn't intend for John to take the rap. It just worked out that style."

Soon later on the Spenkelink execution, onetime San Francisco official Dan White received a prison sentence of seven years and 8 months in prison for killing two people—the Mayor of San Francisco and another city official.

Anyone who follows the news tin signal to similar disparities. Would the outcome be much unlike if we decided for life or death by rolling dice or spinning a roulette wheel?

4. The expiry penalty gives some of the worst offenders publicity that they practice not deserve. Gary Gilmore and Steven Judy received reams of publicity as they neared their dates with the grim reaper. They had a adventure to expound before a national audience their ideas about criminal offense and penalty, God and state, and anything else that happened to cross their minds. Information technology is hard to imagine ii men less deserving of a wide audience. It can be argued, of grade, that if executions become every bit widespread and frequent as proponents of the death penalty hope, the publicity for each murderer volition decline. That may be so, but each may all the same be a media glory on a statewide ground.

While the death sentence undoubtedly deters some would-be murderers, there is evidence that information technology encourages others— peculiarly the unstable who are attracted to media immortality like moths to a flame. If instead of facing heady weeks before television receiver cameras, they faced a lifetime of obscurity in prison house, the path of violence might seem less glamorous to them.

5. The expiry penalisation involves medical doctors, who are sworn to preserve life, in the deed of killing. This issue has been much discussed in contempo years because several states have provided for execution past lethal injection. In 1980 the American Medical Clan, responding to this innovation, declared that a medico should not participate in an execution. Only it added that a dr. may make up one's mind or certify death in whatever situation.

The A.M.A. evaded a major function of the ethical problem. When doctors use their stethoscopes to bespeak whether the electric chair has done its job, they are assisting the executioner.

6. Executions have a corrupting outcome on the public. Thomas Macaulay said of the Puritans that they "hated bear-baiting, not considering it gave pain to the comport, simply because it gave pleasure to the spectators." While incorrect on the showtime point, they were right on the 2d. There is something indecent in the rituals that surround executions and the excitement—fifty-fifty the entertainment—that they provide to the public. There is the true cat-and-mouse ritual of the appeals procedure, with prisoners sometimes led right upward to the execution chamber and then given a stay of execution. There are the terminal visits from family unit, the last dinner, the terminal walk, the last words. Television cameras, which have fought their way into courtrooms and almost everywhere else, may some twenty-four hours push their way right upward to the execution chamber and give us all, in living color, the very last moments.

7. The capital punishment cannot be express to the worst cases. Many people who oppose majuscule punishment have second thoughts whenever a particularly savage murder occurs. When a Richard Speck or Charles Manson or Steven Judy emerges, there is a trend to say, "That 1 really deserves to die." Disgust, acrimony and genuine fright support the second thoughts.

But it is impossible to write a death sentence constabulary in such a way that it will utilise only to the Specks and Mansons and Judys of this world. And, given the ingenuity of the best lawyers money tin buy, there is probably no manner to apply it to the worst murderers who happen to be wealthy.

The death penalty, like every other class of violence, is extremely hard to limit once the "hard cases" persuade society to allow down the bars in guild to solve a few specific issues. A judgement intended for Charles Manson is passed instead on J.D. Gleaton, a semiliterate on South Carolina'due south death row who had difficulty understanding his trial. Later he said: "I don't know annihilation about the police that much and when they are up at that place speaking those big words, I don't even know what they are saying." Or Thomas Hays, under sentence of death in Oklahoma and described by a young man inmate as "nutty as a fruit cake." Before his crime, Mr. Hays was committed to mental hospitals several times; afterwards, he was diagnosed equally a paranoid schizophrenic.

8. The death punishment is an expression of the accented power of the land; abolition of that penalty is a much- needed limit on government ability. What makes the land so pure that information technology has the right to have life? Await at the record of governments throughout history—so often operating with deception, cruelty and greed, then frequently becoming masters of the citizens they are supposed to serve. "Forbidding a man'south execution," Camus said, "would amount to proclaiming publicly that social club and the land are not absolute values." Information technology would corporeality to maxim that there are some things even the country may not do.

There is also the problem of the country's involving innocent people in a premeditated killing. "I'chiliad personally opposed to killing and violence," said the prison warden who had to arrange Gary Gilmore'south execution, "and having to practice that is a difficult responsibility." As well often, in killing and violence, the state compels people to act confronting their consciences.

And in that location is the indicate that government should not requite bad instance—especially not to children. Earl Charles, a veteran of several years on decease row for crimes he did non commit, tried to explain this concluding year: "Well, it is difficult for me to sit downwardly and talk to my son about 'k shalt non impale,' when the state itself...is proverb, 'Well, yes, we can kill, under sure circumstances.' " With great understatement, Mr. Charles added, "That is difficult. I hateful, that is disruptive to him."

ix. There are strong religious reasons for many to oppose the death penalisation. Some find compelling the thought that Cain, the offset murderer, was not executed simply was marked with a special sign and made a wanderer upon the face of the earth. Richard Viguerie developed his position on capital punishment past request what Christ would say and do almost it. "I believe that a strong example can exist made," Mr. Viguerie wrote in a recent book, "that Christ would oppose the killing of a human as penalty for a offense." This view is supported by the New Testament story about the adult female who faced execution by stoning (John viii:7, "He that is without sin amid y'all, allow him cast the first rock").

Former Senator Harold Hughes (D., Iowa), arguing confronting the death sentence in 1974, declared: "'K shalt not kill' is the shortest of the Ten Commandments, unproblematic by qualification or exception....It is equally clear and awesomely commanding as the powerful thrust of chain lightning out of a dark summer heaven."

ten. Fifty-fifty the guilty have a right to life. Leszek Syski is a Maryland antiabortion activist who says that he "became convinced that the question of whether or not murderers deserve to dice is the wrong one. The existent question is whether other humans accept a correct to kill them." He concluded that they practise not after conversations with an opponent of death sentence who asked, "Why don't we torture prisoners? Torturing them is less than killing them." Mr. Syski believes that "torture is dehumanizing, only majuscule punishment is the essence of dehumanization."

Richard Viguerie reached his positions on abortion and death sentence independently, but does see a connection betwixt the two issues: "To me, life is sacred," Mr. Viguerie says. "And I don't believe I accept a right to terminate someone else'southward life either way—by abortion or capital punishment." Many others in the prolife movement have come up to the same conclusion. They don't remember they have a correct to play God, and they don't believe that the country encourages respect for life when it engages in premediated killing.

Camus was correct: We know enough to say that some crimes crave severe punishment. We do not know plenty to say when anyone should dice.

Source: https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/1982/11/20/10-reasons-oppose-death-penalty

0 Response to "Why the Death Penalty Is Not Better for Families"

Post a Comment