Hat Can You Know About the Social Structure and Hierarchy of Hammurapis Babylonian Kingdom?

| Hammurabi 𒄩𒄠𒈬𒊏𒁉 | |

|---|---|

| King of Babylon King of the 4 Corners of the World | |

Hammurabi (standing), depicted as receiving his royal insignia from Shamash (or possibly Marduk). Hammurabi holds his hands over his mouth as a sign of prayer[1] (relief on the upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws). | |

| Rex of the Quondam Babylonian Empire | |

| Reign | 42 years; c. 1792 – c. 1750 BC (centre) |

| Predecessor | Sin-Muballit |

| Successor | Samsu-iluna |

| Born | c. 1810 BC Babylon |

| Died | c. 1750 BC middle chronology (modern-24-hour interval Iraq) (aged c. 60) Babylon |

| Issue | Samsu-iluna |

Hammurabi [a] (c. 1810 – c. 1750 BC) was the 6th king of the First Babylonian dynasty of the Amorite tribe,[two] reigning from c. 1792 BC to c. 1750 BC (according to the Heart Chronology). He was preceded past his father, Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to declining health. During his reign, he conquered Elam and the city-states of Larsa, Eshnunna, and Mari. He ousted Ishme-Dagan I, the rex of Assyria, and forced his son Mut-Ashkur to pay tribute, bringing about all of Mesopotamia nether Babylonian rule.[iii]

Hammurabi is all-time known for having issued the Lawmaking of Hammurabi, which he claimed to have received from Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice. Different before Sumerian law codes, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu, which had focused on compensating the victim of the crime, the Law of Hammurabi was 1 of the first law codes to identify greater accent on the physical punishment of the perpetrator. It prescribed specific penalties for each crime and is among the first codes to institute the presumption of innocence. Although its penalties are extremely harsh past modern standards, they were intended to limit what a wronged person was permitted to do in retribution. The Code of Hammurabi and the Police force of Moses in the Torah incorporate numerous similarities.

Hammurabi was seen past many as a god within his own lifetime. After his death, Hammurabi was revered equally a corking conqueror who spread culture and forced all peoples to pay obeisance to Marduk, the national god of the Babylonians. Later, his military accomplishments became de-emphasized and his role as the ideal lawgiver became the primary attribute of his legacy. For later Mesopotamians, Hammurabi's reign became the frame of reference for all events occurring in the distant past. Even afterwards the empire he built collapsed, he was all the same revered equally a model ruler, and many kings across the Almost East claimed him as an ancestor. Hammurabi was rediscovered by archaeologists in the late nineteenth century and has since been seen as an of import figure in the history of law.

Reign and conquests

Map showing the Babylonian territory upon Hammurabi's ascension in c. 1792 BC and upon his death in c. 1750 BC

Hammurabi was an Amorite Outset Dynasty rex of the metropolis-country of Babylon, and inherited the power from his father, Sin-Muballit, in c. 1792 BC.[4] Babylon was one of the many largely Amorite ruled city-states that dotted the central and southern Mesopotamian plains and waged state of war on each other for control of fertile agronomical land.[5] Though many cultures co-existed in Mesopotamia, Babylonian civilisation gained a degree of prominence amid the literate classes throughout the Middle Due east under Hammurabi.[6] The kings who came before Hammurabi had founded a relatively minor City State in 1894 BC, which controlled footling territory outside of the city itself. Babylon was overshadowed past older, larger, and more powerful kingdoms such every bit Elam, Assyria, Isin, Eshnunna, and Larsa for a century or then later on its founding. However, his begetter Sin-Muballit had begun to consolidate dominion of a small surface area of due south primal Mesopotamia nether Babylonian hegemony and, past the time of his reign, had conquered the minor city-states of Borsippa, Kish, and Sippar.[6]

Thus Hammurabi ascended to the throne as the male monarch of a minor kingdom in the midst of a complex geopolitical situation. The powerful kingdom of Eshnunna controlled the upper Tigris River while Larsa controlled the river delta. To the eastward of Mesopotamia lay the powerful kingdom of Elam, which regularly invaded and forced tribute upon the small states of southern Mesopotamia. In northern Mesopotamia, the Assyrian rex Shamshi-Adad I, who had already inherited centuries onetime Assyrian colonies in Asia Minor, had expanded his territory into the Levant and central Mesopotamia,[seven] although his untimely expiry would somewhat fragment his empire.[8]

The get-go few years of Hammurabi'south reign were quite peaceful. Hammurabi used his power to undertake a series of public works, including heightening the city walls for defensive purposes, and expanding the temples.[9] In c. 1701 BC, the powerful kingdom of Elam, which straddled important trade routes across the Zagros Mountains, invaded the Mesopotamian plain.[10] With allies among the plain states, Elam attacked and destroyed the kingdom of Eshnunna, destroying a number of cities and imposing its dominion on portions of the plain for the first time.[11]

A limestone votive monument from Sippar, Iraq, dating to c. 1792 – c. 1750 BC showing Rex Hammurabi raising his correct arm in worship, at present held in the British Museum

This bust, known as the "Caput of Hammurabi", is at present thought to predate Hammurabi past a few hundred years[12] (Louvre)

In order to consolidate its position, Elam tried to offset a state of war betwixt Hammurabi's Babylonian kingdom and the kingdom of Larsa.[13] Hammurabi and the king of Larsa made an alliance when they discovered this duplicity and were able to shell the Elamites, although Larsa did not contribute profoundly to the military effort.[13] Angered by Larsa'south failure to come to his aid, Hammurabi turned on that southern power, thus gaining control of the entirety of the lower Mesopotamian plain by c. 1763 BC.[14]

Equally Hammurabi was assisted during the war in the south past his allies from the north such as Yamhad and Mari, the absence of soldiers in the north led to unrest.[14] Standing his expansion, Hammurabi turned his attention northward, quelling the unrest and shortly after crushing Eshnunna.[15] Next the Babylonian armies conquered the remaining northern states, including Babylon'due south former ally Mari, although information technology is possible that the conquest of Mari was a surrender without whatsoever actual conflict.[sixteen] [17] [18]

Hammurabi entered into a protracted state of war with Ishme-Dagan I of Assyria for control of Mesopotamia, with both kings making alliances with minor states in social club to gain the upper hand. Eventually Hammurabi prevailed, ousting Ishme-Dagan I just earlier his own expiry. Mut-Ashkur, the new rex of Assyria, was forced to pay tribute to Hammurabi.

In just a few years, Hammurabi succeeded in uniting all of Mesopotamia under his rule.[18] The Assyrian kingdom survived but was forced to pay tribute during his reign, and of the major city-states in the region, only Aleppo and Qatna to the due west in the Levant maintained their independence.[18] However, i stele of Hammurabi has been plant every bit far n as Diyarbekir, where he claims the championship "Male monarch of the Amorites".[19]

Vast numbers of contract tablets, dated to the reigns of Hammurabi and his successors, take been discovered, as well equally 55 of his own letters.[20] These letters give a glimpse into the daily trials of ruling an empire, from dealing with floods and mandating changes to a flawed calendar, to taking intendance of Babylon's massive herds of livestock.[21] Hammurabi died and passed the reins of the empire on to his son Samsu-iluna in c. 1750 BC, under whose rule the Babylonian empire apace began to unravel.[22]

Code of laws

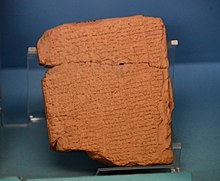

Police force lawmaking of Hammurabi, a smaller version of the original law code stele. Terracotta tablet, from Nippur, Iraq, c. 1790 BC. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul

The Lawmaking of Hammurabi is non the primeval surviving law code;[23] it is predated past the Code of Ur-Nammu, the Laws of Eshnunna, and the Code of Lipit-Ishtar.[23] Yet, the Code of Hammurabi shows marked differences from these before law codes and ultimately proved more than influential.[24] [25] [23]

The Code of Hammurabi was inscribed on a stele and placed in a public place so that all could see it, although it is idea that few were literate. The stele was afterward plundered by the Elamites and removed to their upper-case letter, Susa; information technology was rediscovered there in 1901 in Iran and is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris. The code of Hammurabi contains 282 laws, written past scribes on 12 tablets. Dissimilar earlier laws, it was written in Akkadian, the daily language of Babylon, and could therefore exist read by any literate person in the urban center.[24] Earlier Sumerian police force codes had focused on compensating the victim of the offense,[25] but the Lawmaking of Hammurabi instead focused on physically punishing the perpetrator.[25] The Code of Hammurabi was 1 of the first police force lawmaking to place restrictions on what a wronged person was allowed to do in retribution.[25]

The construction of the code is very specific, with each offense receiving a specified penalty. The punishments tended to be very harsh past modern standards, with many offenses resulting in death, disfigurement, or the apply of the "Center for eye, tooth for tooth" (Lex Talionis "Police of Retaliation") philosophy.[26] [25] The lawmaking is also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, and it also suggests that the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide testify.[27] However, there is no provision for extenuating circumstances to alter the prescribed punishment.

A etching at the top of the stele portrays Hammurabi receiving the laws from Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice,[28] and the preface states that Hammurabi was chosen past Shamash to bring the laws to the people.[29] Parallels betwixt this narrative and the giving of the Covenant Code to Moses by Yahweh atop Mount Sinai in the Biblical Book of Exodus and similarities betwixt the two legal codes propose a common ancestor in the Semitic background of the 2.[thirty] [31] [32] [33] Withal, fragments of previous constabulary codes have been plant and information technology is unlikely that the Mosaic laws were straight inspired by the Lawmaking of Hammurabi.[xxx] [31] [32] [33] [b] Some scholars take disputed this; David P. Wright argues that the Jewish Covenant Lawmaking is "directly, primarily, and throughout" based upon the Laws of Hammurabi.[34] In 2010, a team of archaeologists from Hebrew University discovered a cuneiform tablet dating to the eighteenth or seventeenth century BC at Hazor in Israel containing laws conspicuously derived from the Code of Hammurabi.[35]

Legacy

Celebration after his decease

Hammurabi was honored to a higher place all other kings of the 2nd millennium BC[36] and he received the unique laurels of beingness alleged to be a god inside his own lifetime.[37] The personal name "Hammurabi-ili" meaning "Hammurabi is my god" became mutual during and after his reign. In writings from shortly afterward his death, Hammurabi is commemorated mainly for 3 achievements: bringing victory in war, bringing peace, and bringing justice.[37] Hammurabi's conquests came to be regarded as part of a sacred mission to spread civilization to all nations.[38] A stele from Ur glorifies him in his ain vocalization as a mighty ruler who forces evil into submission and compels all peoples to worship Marduk.[39] The stele declares: "The people of Elam, Gutium, Subartu, and Tukrish, whose mountains are distant and whose languages are obscure, I placed into [Marduk's] hand. I myself continued to put straight their confused minds." A later hymn as well written in Hammurabi'southward own voice extols him every bit a powerful, supernatural force for Marduk:[38]

Tablet of Hammurabi (𒄩𒄠𒈬𒊏𒁉, fourth line from the top), King of Babylon. British Museum.[40] [41] [42]

I am the king, the brace that grasps wrongdoers, that makes people of ane listen,

I am the smashing dragon among kings, who throws their counsel in disarray,

I am the net that is stretched over the enemy,

I am the fright-inspiring, who, when lifting his violent eyes, gives the ill-behaved the capital punishment,

I am the great internet that covers evil intent,

I am the young lion, who breaks nets and scepters,

I am the battle net that catches him who offends me.[39]

After extolling Hammurabi's military machine accomplishments, the hymn finally declares: "I am Hammurabi, the king of justice."[37] In later commemorations, Hammurabi's function as a dandy lawgiver came to be emphasized above all his other accomplishments and his military achievements became de-emphasized. Hammurabi'southward reign became the point of reference for all events in the afar by. A hymn to the goddess Ishtar, whose language suggests it was written during the reign of Ammisaduqa, Hammurabi'southward fourth successor, declares: "The king who offset heard this vocal every bit a vocal of your heroism is Hammurabi. This song for you was composed in his reign. May he be given life forever!"[36] For centuries after his death, Hammurabi's laws continued to be copied by scribes as part of their writing exercises and they were even partially translated into Sumerian.[43]

Political legacy

Copy of Hammurabi'southward stele usurped by Shutruk-Nahhunte I. The stele was only partially erased and was never re-inscribed.[44]

During the reign of Hammurabi, Babylon usurped the position of "most holy city" in southern Mesopotamia from its predecessor, Nippur.[45] Under the rule of Hammurabi's successor Samsu-iluna, the brusque-lived Babylonian Empire began to collapse. In northern Mesopotamia, both the Amorites and Babylonians were driven from Assyria by Puzur-Sin a native Akkadian-speaking ruler, c. 1740 BC. Around the same time, native Akkadian speakers threw off Amorite Babylonian rule in the far southward of Mesopotamia, creating the Sealand Dynasty, in more or less the region of ancient Sumer. Hammurabi'southward ineffectual successors met with further defeats and loss of territory at the easily of Assyrian kings such equally Adasi and Bel-ibni, as well equally to the Sealand Dynasty to the south, Elam to the e, and to the Kassites from the northeast. Thus was Babylon quickly reduced to the small and minor state it had once been upon its founding.[46]

The insurrection de grace for the Hammurabi'due south Amorite Dynasty occurred in 1595 BC, when Babylon was sacked and conquered by the powerful Hittite Empire, thereby ending all Amorite political presence in Mesopotamia.[47] Nevertheless, the Indo-European-speaking Hittites did not remain, turning over Babylon to their Kassite allies, a people speaking a linguistic communication isolate, from the Zagros mountains region. This Kassite Dynasty ruled Babylon for over 400 years and adopted many aspects of the Babylonian culture, including Hammurabi's code of laws.[47] Even after the autumn of the Amorite Dynasty, however, Hammurabi was still remembered and revered.[43] When the Elamite king Shutruk-Nahhunte I raided Babylon in 1158 BC and carried off many rock monuments, he had most of the inscriptions on these monuments erased and new inscriptions carved into them.[43] On the stele containing Hammurabi'south laws, however, simply four or five columns were wiped out and no new inscription was ever added.[44] Over a thousand years after Hammurabi'southward death, the kings of Suhu, a country forth the Euphrates river, just northwest of Babylon, claimed him as their ancestor.[48]

Modern rediscovery

The bas-relief of Hammurabi at the U.s. Congress

In the late nineteenth century, the Lawmaking of Hammurabi became a major center of debate in the heated Babel und Bibel ("Babylon and Bible") controversy in Frg over the relationship between the Bible and ancient Babylonian texts.[49] In January 1902, the German Assyriologist Friedrich Delitzsch gave a lecture at the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin in front of the Kaiser and his married woman, in which he argued that the Mosaic Laws of the Erstwhile Attestation were directly copied off the Lawmaking of Hammurabi.[50] Delitzsch'southward lecture was and then controversial that, by September 1903, he had managed to collect 1,350 brusque articles from newspapers and journals, over 300 longer ones, and 20-eight pamphlets, all written in response to this lecture, as well as the preceding one about the Overflowing story in the Epic of Gilgamesh. These articles were overwhelmingly critical of Delitzsch, though a few were sympathetic. The Kaiser distanced himself from Delitzsch and his radical views and, in fall of 1904, Delitzsch was forced to give his third lecture in Cologne and Frankfurt am Main rather than in Berlin.[49] The putative relationship between the Mosaic Police force and the Lawmaking of Hammurabi later became a major part of Delitzsch's argument in his 1920–21 book Die große Täuschung (The Bang-up Deception) that the Hebrew Bible was irredeemably contaminated by Babylonian influence and that simply by eliminating the human One-time Testament entirely could Christians finally believe in the true, Aryan message of the New Testament.[50] In the early on twentieth century, many scholars believed that Hammurabi was Amraphel, the Male monarch of Shinar in the Book of Genesis fourteen:1.[51] [52] This view has at present been largely rejected,[53] [54] and Amraphael'south existence is not attested in any writings from exterior the Bible.[54]

Because of Hammurabi'south reputation as a lawgiver, his delineation tin be found in several U.s.a. government buildings. Hammurabi is i of the 23 lawgivers depicted in marble bas-reliefs in the chamber of the U.Due south. House of Representatives in the United States Capitol.[55] A frieze by Adolph Weinman depicting the "great lawgivers of history", including Hammurabi, is on the due south wall of the U.S. Supreme Court edifice.[56] [57] At the time of Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi Army's 1st Hammurabi Armoured Partition was named later the ancient king as part of an effort to emphasize the connectedness betwixt modern Iraq and the pre-Arab Mesopotamian cultures.

Minor planet 7207 Hammurabi is named in his honour.

See also

- Babylonian constabulary

- Cuneiform law

- Short chronology timeline

- Manusmṛti

Notes

- ^ ; Akkadian: 𒄩𒄠𒈬𒊏𒁉 Ḫa-am-mu-ra-bi, from the Amorite ʻAmmurāpi ("the kinsman is a healer"), itself from ʻAmmu ("paternal kinsman") and Rāpi ("healer").

- ^ Barton, a onetime professor of Semitic languages at the University of Pennsylvania, stated that while in that location are similarities betwixt the 2 texts, a study of the entirety of both laws "convinces the educatee that the laws of the Old Attestation are in no essential way dependent upon the Babylonian laws." He states that "such resemblances" arose from "a similarity of antecedents and of full general intellectual outlook" between the ii cultures, but that "the hit differences show that at that place was no direct borrowing."[31]

References

- ^ Roux, Georges (27 August 1992), "The Time of Confusion", Ancient Iraq, Penguin Books, p. 266, ISBN9780141938257

- ^ "Hammurabi | Biography, Code, Importance, & Facts".

- ^ Brook, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction . Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN978-0-395-87274-1. OCLC 39762695.

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, p. one

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 1–two

- ^ a b Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 3

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. three–four

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 16

- ^ Arnold 2005, p. 43

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 15–16

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 17

- ^ Claire, Iselin. "Purple head, known as the "Head of Hammurabi"". Musée du Louvre.

- ^ a b Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 18

- ^ a b Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 31

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 40–41

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 54–55

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 64–65

- ^ a b c Arnold 2005, p. 45

- ^ Clay, Albert Tobias (1919). The Empire of the Amorites. Yale Academy Press. p. 97.

- ^ Breasted 2003, p. 129

- ^ Breasted 2003, pp. 129–130

- ^ Arnold 2005, p. 42

- ^ a b c Davies, W. W. (Jan 2003). Codes of Hammurabi and Moses. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN978-0-7661-3124-eight. OCLC 227972329.

- ^ a b Breasted 2003, p. 141

- ^ a b c d e Bertman, Stephen (2003). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 71. ISBN978-019-518364-1.

- ^ Prince, J. Dyneley (1904). "The Code of Hammurabi". The American Periodical of Theology. viii (3): 601–609. doi:10.1086/478479. JSTOR 3153895.

- ^ Victimology: Theories and Applications, Ann Wolbert Burgess, Albert R. Roberts, Cheryl Regehr, Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2009, p. 103

- ^ Kleiner, Fred South. (2010). Gardner's Fine art through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Vol. one (Thirteenth ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 29. ISBN978-0-495-57360-9.

- ^ Smith, J. M. Powis (2005). The Origin and History of Hebrew Police. Clark, New Bailiwick of jersey: The Lawbook Commutation, Ltd. p. thirteen. ISBN978-1-58477-489-ane.

- ^ a b Douglas, J. D.; Tenney, Merrill C. (2011). Zondervan Illustrated Bible Lexicon. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. p. 1323. ISBN978-0310229834.

- ^ a b c Barton, G.A: Archaeology and the Bible. Academy of Michigan Library, 2009, p.406.

- ^ a b Unger, M.F.: Archeology and the Old Attestation. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing Co., 1954, p.156, 157

- ^ a b Free, J.P.: Archæology and Biblical History. Wheaton: Scripture Press, 1950, 1969, p. 121

- ^ Wright, David P. (2009). Inventing God's Law: How the Covenant Code of the Bible Used and Revised the Laws of Hammurabi . Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. iii and passim. ISBN978-0-19-530475-6.

- ^ "Tablet Discovered by Hebrew U Matches Code of Hammurabi". Beit El: HolyLand Holdings, Ltd. Arutz Sheva. 26 June 2010.

- ^ a b Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 127.

- ^ a b Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 126.

- ^ a b Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Cuneiform Tablets in the British Museum (PDF). British Museum. 1905. pp. Plates 44 and 45.

- ^ Budge, E. A. Wallis (Ernest Alfred Wallis); King, L. West. (Leonard William) (1908). A guide to the Babylonian and Assyrian antiquities. London : Printed by the order of the Trustees. p. 147.

- ^ For full transcription: "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 129.

- ^ a b Van De Mieroop 2005, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Schneider, Tammi J. (2011), An Introduction to Ancient Mesopotamian Organized religion, Yard Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdman'southward Publishing Company, pp. 58–59, ISBN978-0-8028-2959-7

- ^ Georges Roux – Aboriginal Iraq

- ^ a b DeBlois 1997, p. 19

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2005, p. 130.

- ^ a b Ziolkowski 2012, p. 25.

- ^ a b Ziolkowski 2012, pp. 23–25.

- ^ "AMRAPHEL - JewishEncyclopedia.com".

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: Genesis xiv - New International Version".

- ^ N, Robert (1993). "Abraham". In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN978-0-xix-504645-8.

- ^ a b Granerød, Gard (26 March 2010). Abraham and Melchizedek: Scribal Activity of 2nd Temple Times in Genesis fourteen and Psalm 110. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. p. 120. ISBN978-3-xi-022346-0.

- ^ "Hammurabi". Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ "Courtroom Friezes" (PDF). Supreme Court of the United States. Archived from the original (PDF) on one June 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (11 March 1998). "Lawgivers: From Two Friezes, Great Figures of Legal History Gaze Upon the Supreme Court Demote". WP Company LLC. The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

Sources

- Arnold, Bill T. (2005). Who Were the Babylonians?. Brill Publishers. ISBN978-xc-04-13071-5. OCLC 225281611.

- Breasted, James Henry (2003). Ancient Fourth dimension or a History of the Early on Globe, Role 1. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN978-0-7661-4946-v. OCLC 69651827.

- DeBlois, Lukas (1997). An Introduction to the Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-12773-eight. OCLC 231710353.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (2005). King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN978-ane-4051-2660-1. OCLC 255676990.

- Ziolkowski, Theodore (2012), Gilgamesh amongst Us: Modernistic Encounters with the Ancient Ballsy, Ithaca, New York and London, England: Cornell University Printing, ISBN978-0-8014-5035-viii

Farther reading

- Finet, André (1973). Le trone et la rue en Mésopotamie: L'exaltation du roi et les techniques de l'opposition, in La voix de l'opposition en Mésopotamie. Bruxelles: Institut des Hautes Études de Belgique. OCLC 652257981.

- Jacobsen, Th. (1943). "Primitive republic in Ancient Mesopotamia". Journal of Most Eastern Studies. 2 (3): 159–172. doi:10.1086/370672. S2CID 162148036.

- Finkelstein, J. J. (1966). "The Genealogy of the Hammurabi Dynasty". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 20 (3): 95–118. doi:10.2307/1359643. JSTOR 1359643. S2CID 163803506.

- Hammurabi (1952). Commuter, G.R.; Miles, John C. (eds.). The Babylonian Laws. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Leemans, W. F. (1950). The Old Babylonian Merchant: His Business and His Social Position. Leiden: Brill.

- Munn-Rankin, J. M. (1956). "Diplomacy in Southwest asia in the Early Second Millennium BC". Iraq. 18 (ane): 68–110. doi:x.2307/4199599. JSTOR 4199599.

- Pallis, S. A. (1956). The Artifact of Iraq: A Handbook of Assyriology. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard.

- Richardson, K.E.J. (2000). Hammurabi's laws : text, translation and glossary. Sheffield: Sheffield Acad. Press. ISBN978-ane-84127-030-2.

- Saggs, H.W.F. (1988). The greatness that was Babylon : a survey of the ancient culture of the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN978-0-283-99623-8.

- Yoffee, Norman (1977). The economical role of the crown in the onetime Babylonian period. Malibu, CA: Undena Publications. ISBN978-0-89003-021-9.

External links

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hammurabi |

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hammurabi. |

- A Closer Expect at the Code of Hammurabi (Louvre museum)

- Works by Hammurabi at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or near Hammurabi at Internet Archive

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hammurabi

0 Response to "Hat Can You Know About the Social Structure and Hierarchy of Hammurapis Babylonian Kingdom?"

Post a Comment